<br>

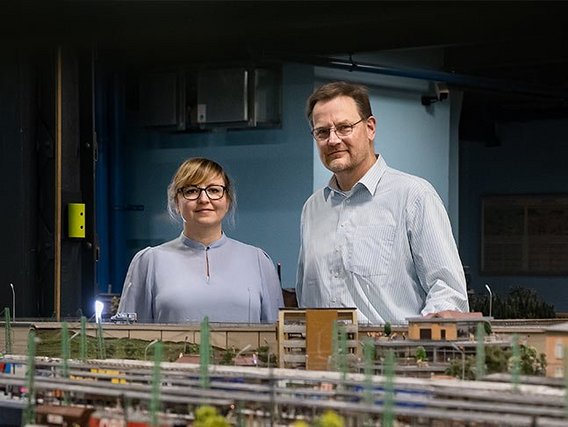

Ms. Leicht, Dr. Vallée, what role does autonomous driving play in road and rail freight transport?

Dr. Hans Vallée: As far as the railways are concerned, trains will not be running autonomously any time soon. There’s no doubt that this would be possible in technical terms. But it isn’t compatible with the operating procedures of rail transport on mainline routes.

What does that mean?

HV: Autonomous means that a vehicle independently looks for its own route. To put it in simple terms, it finds its way wherever there’s space, for example by switching to a trunk road if there’s a traffic jam on the motorway. But that won’t work with the railways. Rail transport is organised centrally: Trains run according to timetables, they can’t simply switch to another route; after all, the rail network isn’t that large in most countries. This means that self-driving trains are only really conceivable in self-contained places. These would include depots or marshalling yards, when the task at hand is to sort wagons autonomously – and this is going to be possible with the help of the digital automatic coupling system (DAC), which Deutsche Bahn is soon going to be switching over to for freight transport operations.

Ms. Leicht, what’s the situation with self-driving freight transport by road?

Katrin Leicht: When it comes to distinguishing between autonomous and automated traffic on the road, we follow the SAE autonomy levels. A level 5 vehicle would be completely autonomous; in this case, the system would take over all the driving tasks. In practice, however, this level is going to be a pipe dream for the foreseeable future, even in freight transport, because it would mean that a cargo vehicle would have to find its way on any terrain, in all traffic scenarios and under all possible environmental conditions. And this is where the technology bumps up against its limits, at least at the moment.